[Anchor buttons for each model]

Over the decades, several authors have reached for the ladder metaphor to illustrate their perceptions of the participatory process. Arnstein’s (1971) is the original iteration; conceived as a tool for citizen involvement in decision-making, it offers a critique of the political process of engagement. It was more than twenty years before Hart (1992) published a refined version of Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation; this time annotated with the roles of children and young people as the focus. Others have followed although not originally represented as ladders; for the sake of ease of comparison we have placed some of them in the ladder format.

The use of a ladder to represent the participation process is a useful visual metaphor, or device, for a range of reasons:

Seeing an objective that is out of reach requires an access plan

All plans need resources, in this case a ladder

It signifies aspiration, seeking a higher perspective

A ladder provides access to something beyond immediate reach

Ascending indicates a sense of escalation, of getting higher

Each step up is progress towards a goal

Reaching the top is an achievement but does it reach the objective?

Common themes across all of the ladders, or more accurately typologies, is the progression from the passive to the active: from people being mere receivers of information (at best); through to critical citizen engagement and collaborative action.

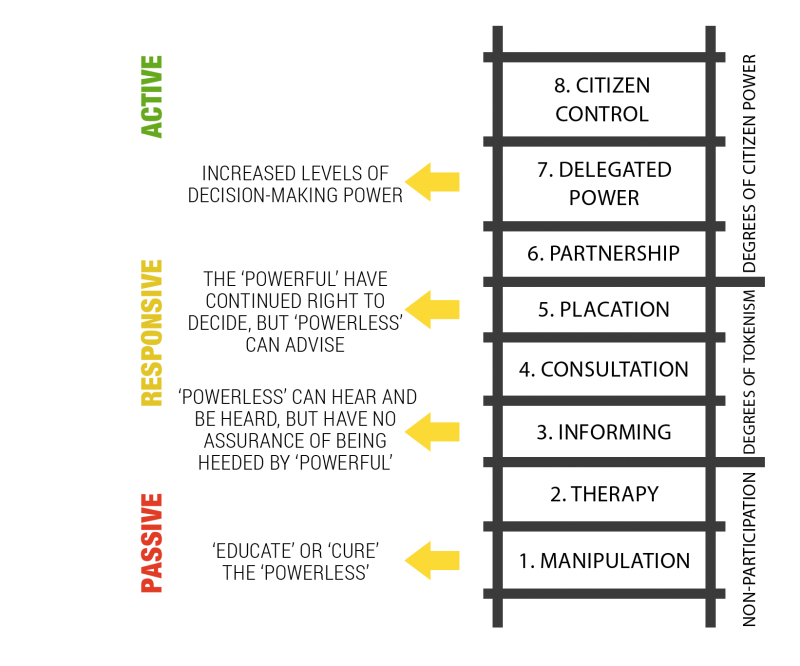

Probably one of the most well known models of participation is that of Sherry Arnstein, called the Ladder of Citizen’s Participation, published in 1969 in the house Journal of the American Planning Association. This model is one of the most often cited on the process of participation; though usually within the context of Roger Hart’s much later version. It has informed and influenced a wide variety of fields of study and of practice. For those working in the public sector, private sector and business, or those involved in grass roots community development, Arnstein’s model is one that is at once easily understandable as well as clear in terms of how to implement simple steps in order to demonstrate active citizen involvement.

However, in order to understand the model we must first appreciate what Arnstein meant by ‘citizen power’. It is crucial to know that this model was developed in 1960’s America, and within that it holds a number of assumptions that are related to that specific context: this is the era of the citizenry questioning their country’s involvement in the Vietnam war; the challenge of the Civil Rights Movement and the quest for electoral emancipation by African Americans; an alternative political narrative questioning the privileging of male hegemony from a feminist critique; and a general unease at the assassination of key political figures such as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and John and Robert Kennedy.

Arnstein locates her theory around a stated declaration that citizen participation is citizen power specifically. Her model enables participants to identify who has power when important decisions are being made; the process of doing this means that those involved can become true co-creators of decision making, which illustrates Arnstein’s argument that participation cannot be had without sharing and re-distributing power.

Understanding participation as described and defined by Arnstein involves understanding power: basically, the ability of the different parties to achieve what they identify as their goals. A major factor in full participative models is power, who has it and who determines who has access to it. Additionally, it depends on two commodities: information and money. Participation also depends on people’s confidence and skills. Many organizations may be unwilling to ‘allow’ people to participate as they mistakenly fear loss of control (an argument later advanced by Pretty): they believe that power is finite, that there is only so much power to share around, thus the equation goes that giving away power may mean losing your own. Using Arnstein’s model, we suggest that there are many situations when working together allows everyone to achieve more than they could on their own.

Essentially, the model is a powerful process that seeks to empower people to take charge of their lives and their surroundings. What we hope to demonstrate is the applicability of the model to all of those practitioners concerned with a practice that can and should be participative.

The ladder is a guide to identifying who has power when important decisions are being made. Its longevity as a practical model attests to communities of interest wishing to consider alternatives that confront the perceived status quo, and challenge processes that refuse to consider anything beyond the bottom rungs.

Below is a brief description of the eight rungs/steps of the ladder:

![]()

Arnstein, S. (1971) ‘A Ladder of Citizen’s Participation’, Journal of the American Institute of Planners, no 35, July.

Now let us consider some later variations on the ladder model.

Hart, R. (1992) Children’s Participation: From Tokenism to Citizenship, UNICEF Innocenti Essays No. 4, Florence: UNICEF.

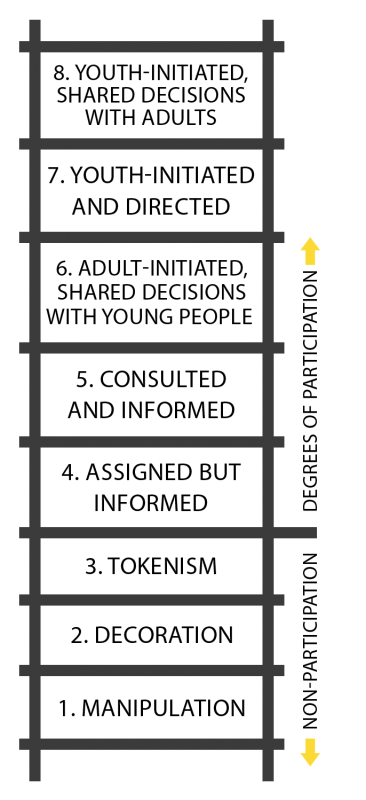

Roger Hart acknowledged and built on Sherry Arnstein’s model, to develop a ladder of participation applicable to those who work with children and young people, which is often referred to as the ladder of youth participation. In his seminal work on this subject, Hart wrote his essay for a wide audience:

This Essay is written for people who know that young people have something to say but who would like to reflect further on the process. It is also written for those people who have it in their power to assist children in having a voice, but who, unwittingly or not, trivialize their involvement. (Hart, 1992: 4)

Located within this apparently simplistic construct is a sophisticated, some might even argue radical, process of engagement designed to include and involve all members of the community.

In order to fully appreciate Hart’s ladder it is first essential to understand the definition of child. According to the U.N. Convention on the Rights of the Child, ‘child’ is a term that covers anyone up to the age of 18. In this section we will be referring to the term young person to denote the same.

Hart suggests that you can measure the health of a nation by the way that it involves its citizens in the democratic process, especially at the community grassroots level. He also states that this is an on-going project; one that must be taught, and experienced at at early age so that it becomes expected at a later age. A nation that is already sure of its democratic stance should be able to easily identify how it listens to and works with its children and young people.

He further suggests that “confidence and competence to be involved must be gradually acquired through practice” (ibid). It is not sufficient to simply co-opt a young person, or adult for that matter, onto a group and expect them to deliver competent and credible decision-making immediately.

However, it is also Hart’s assertion that although there are many well established democratic societies and nations, where children’s rights are well established, all too often participation is either “exploitative or frivolous” (ibid).

Hart’s ladder ascends in sequence: the bottom three rungs describe youth involvement that is not true participation; whereas the top five rungs describe genuine engagement and active participation.

8. Child initiated, shared decisions with adults is when projects or programmes are initiated by children and decision-making is shared among children and adults. These projects empower children while at the same time enabling them to access and learn from the life experience and expertise of adults.

7. Child initiated and directed is when young people initiate and direct a project or programme. Adults are involved only in a supportive role.

6. Adult-initiated, shared decisions with children is when projects or programmes are initiated by adults but the decision-making is shared with the young people.

5. Consulted and informed is when children give advice on projects or programmes designed and run by adults. Children are informed about how their input will be used and the outcomes of the decisions made by adults.

4. Assigned but informed is where children are assigned a specific role and informed about how and why they are being involved.

3. Tokenism is where young people appear to be given a voice, but in fact have little or no choice about what they do or how they participate.

2. Decoration is where young people are used to help or “bolster” a cause in a relatively indirect way, although adults do not pretend that the cause is inspired by children.

1.Manipulation is where adults use children to support causes and pretend that the causes are inspired by children.

His ladder deals with the life of children and young people in the public domain, youth groups, schools, community groups, youth councils, etc. all of which are outside of and beyond the family. It could be argued that it is both inspirational and aspirational.

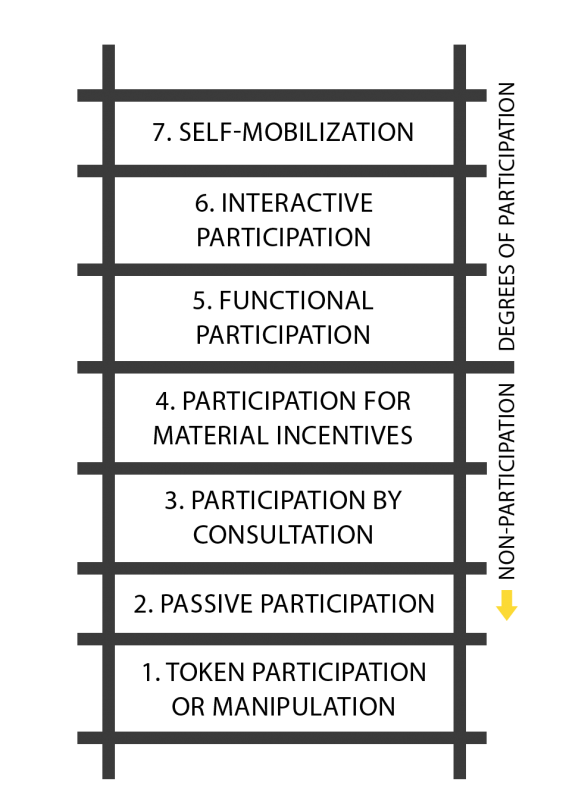

Jules Pretty’s typology is another demonstration of how the participation process is progressive, moving through discrete stages from tokenism to independent action:

Pretty acknowledges the existential threat that moving to the autonomy of self-mobilization poses to hegemonic agents; although it is not put explicitly, it is suggested that what might be required is humility on the part of external professionals that they do not know everything, cannot control everything, should not seek to possess the knowledge of others. Basically, Pretty advances the argument that external agents involved in the participatory process need to acknowledge and value local people as peers. When this was written it was a challenge, particularly to ‘the development community’; even though Arnstein’s (1971) work pre-dates it by almost a quarter of a century. For youth and community workers, the practice of working alongside young people and community groups is a fundamental principle that underpins their work.

Pretty highlighted the inherent tensions within the concept of participation and the dilemma posed for those in authority: that the authorities “both need and fear people’s participation” (1995: 1252). From a need perspective, issues around, for example, resource allocation, or local planning matters, require citizen endorsement to give validity to proposals; conversely, from the fear perspective, citizen engagement, empowerment of the people, is less easily controlled both in terms of their decisions and the management of time. These tensions and dilemmas represent the contradictions within the participatory process: the use of power, either as paternalism or emancipation.

Pretty warned workers engaged in participatory processes that they should “not be intimidated by the complexities and uncertainties of dialogue and action” (1995: 1258). It must also be remembered that not everyone’s voice is heard: attention must be paid to bias that may exclude already marginalized voices. Identifying the range and complexity of constituencies requires honesty and integrity if a process is to be inclusive; criteria that exclude must be challenged, must be changed.

Pretty, J.N. (1995) ‘Participatory Learning for Sustainable Agriculture’, World Development, Vol. 23 (8), 1247 – 1265.

Nazneen Kanji and Laura Greenwood’s ladder is not a progressive construct where a group moves from ‘compliance’ to ‘collective action’ as part of a educative participatory process but rather is an analytic tool for assessing at what stage a given group may be at when the analysis is applied (see Kanji and Greenwood, 2001: 51 – 62 for practical examples). That said, it does offer a useful representation of the discrete phases of participatory engagement, or the lack thereof.

An explanation of Kanji and Greenwood’s typology, exemplified in the ladder graphic, is thus:

Kanji and Greenwood (2001: 5) credit Andrea Cornwall’s earlier work (undated), and that of Sherry Arnstein (1971), for their development of this typology. However, Cornwall and Jewkes (1995) do examine discrete models of participation in the realm of academic research and highlight Stephen Biggs’ (1989) identification of four modes of participation that have a striking similarity to that of Kanji and Greenwood:

Andrea Cornwall and Rachel Jewkes suggest that Biggs’ definitions constitute a “continuum of control” (1995: 1669): highlighting the progression from ‘shallow’ (contractual) to ‘deep’ (collegiate), to emphasise the shift in the power balance. They take the analysis further by reference to Farrington and Bebbington (1993) who introduce the concept of scale, using ‘narrow’ to indicate few people involved, to ‘wide’ where there are many – literally widening participation.

Whilst Biggs has not chosen a ladder as the representational metaphor, we could undoubtedly draw a four-rung ladder to set alongside the others used above. It is suggested that Kanji and Greenwood’s extrapolation from Cornwall may in fact come from the critique offered by Cornwall and Jewkes (1995), in particular Biggs’ modes.

Kanji, N. and Greenwood, L. (2001) Participatory Approaches to Research and Development in IIED: Learning from Experience, London: International Institute for Environment and Development.

Critics of this form of Participation suggest that it is:

What do you think?

As a simple device to illustrate a very complex process the ladder metaphor graphically represents the twin contradictions: the aspiration of access to power and status by the powerless; and the potential for restriction and control by the powerful. This leads to an inevitable question: Does the ladder reach the top and what happens if the space between the rungs is too great?

Acknowledging Freire (1972), the modes identified by both Biggs and Kanji and Greenwood display an awareness, appreciation, and understanding of the relational complexities involved: in simple terms, issues of power, conduct, and intention. From this we can draw parallels with modes and models of participation involving young people and community groups. Where learning is a shared endeavour, understanding is mutual, and new knowledge is co-created.

Having considered these ladder models we would identify one important element that we believe is missing from all: there appears to be no consideration of the role and purpose of critical reflection. Now it could be argued that, like context, reflection is an intrinsic component and therefore does not warrant mention; we would respectfully disagree. Regardless of where on any of the ladders any given group of young people or community participants reach, the contribution that critical reflection brings to the analysis of practice is a significant, maybe even vital, facet of learning that, we would advocate, should be made explicit; perhaps even as an additional rung on a ladder or line in a typology.

And finally, because participation is such a potentially powerful process, a word of warning: if aspiration is unmet the ladders may be used to storm the citadel.

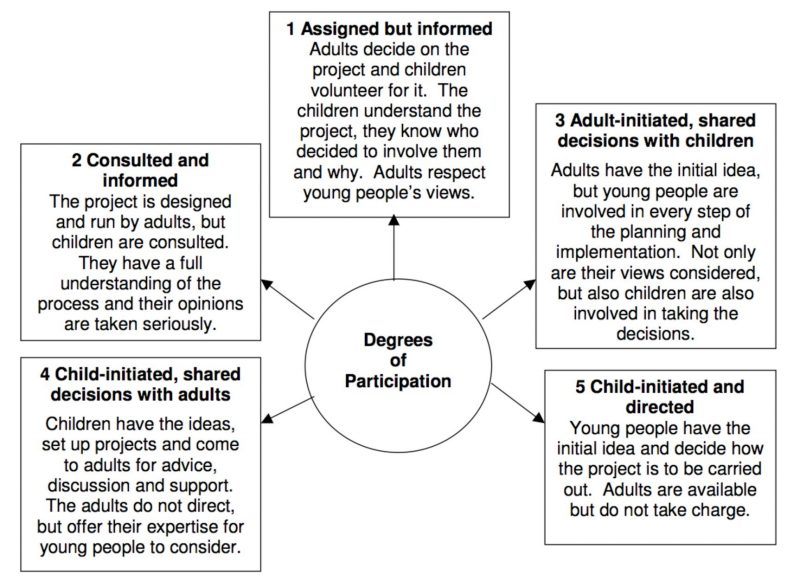

Phil Treseder’s (1997) model is a reimagining of Hart’s ladder into five Degrees of Participation.; it is different in two important ways. Firstly, Treseder moves away from the ladder metaphor, so is better able to offer a critique of the ladder device; he suggests that there is the potential to conceive it as a linear or hierarchical sequence of steps that it is necessary to follow in order to reach the top of the ladder. Secondly, he makes a very strong point that there should be no limit to the involvement of children and young people: rightly, he highlights that time and work needs to be invested so that young people acquire the skills and understanding to fully engage with the processes.

Aside from Hart, Treseder acknowledges that his work was also influenced by David Hodgson’s Participation of children and young people in social work (1995). Hodgson identified five conditions that he considered should be met for successful involvement in participatory practice:

Treseder elaborates five discrete Degrees of Involvement to illustrate the linked stages in the participation process. His model highlights the fact that there is no hierarchy; each element is of equal standing with the others. Which stage, or degree, is chosen depends on the proposed project and the wishes of the children involved; just reaching this stage is itself a sophisticated process. Although Treseder asserts a lack of hierarchy in his intention, inevitably the stages will be interpreted as being progressive; with children acquiring increasing power, adults will see their power diminishing. The objectives of each stage bear a striking resemblance to the work of earlier practitioners, most notably Arnstein and Hart.

Assigned but Informed

This is a description of an adult-chosen and led project where it is clear that children and young people can volunteer and be involved but that the direction and governance of the project is owned by the adults within the dynamic. The children and young people are clear that this is an adult-owned project, and they understand the requirements of their volunteering. It is important to stress that they also know that their views, thoughts and impressions will be listened to and respected.

Adult-initiated, shared decisions with children

Although adults generate the initial ideas, the subsequent phases of planning and implementation actively involve children. At this level, children’s views are considered and they take part in making decisions.

Consulted and Informed

With a project or programme designed and run by adults there remains only consultation as a way of involving children. Being consulted requires comprehension of the proposals and an expectation that views expressed are taken seriously. Consultation differs from participation; it is based on asking, not involving.

Child-initiated and directed

This stage represents a shift in the power balance; children have the original idea and determine what will happen, when, and how. Adults are available but do not control.

Child-initiated, shared decisions with adults

At this stage it is the children who have the ideas, establish the project, and determine when to seek support, advice, and consultation, but not direction, from adults.

Whilst the Model is illustrated below, much more detail can be found in Treseder’s original work (see REFERENCES).

Hodgson, D. (1995) Participation of Children and Young People in Social Work, New York: UNICEF.

Treseder, P. (1997) Empowering children and young people training manual: promoting involvement in decision-making, London: Save the Children.

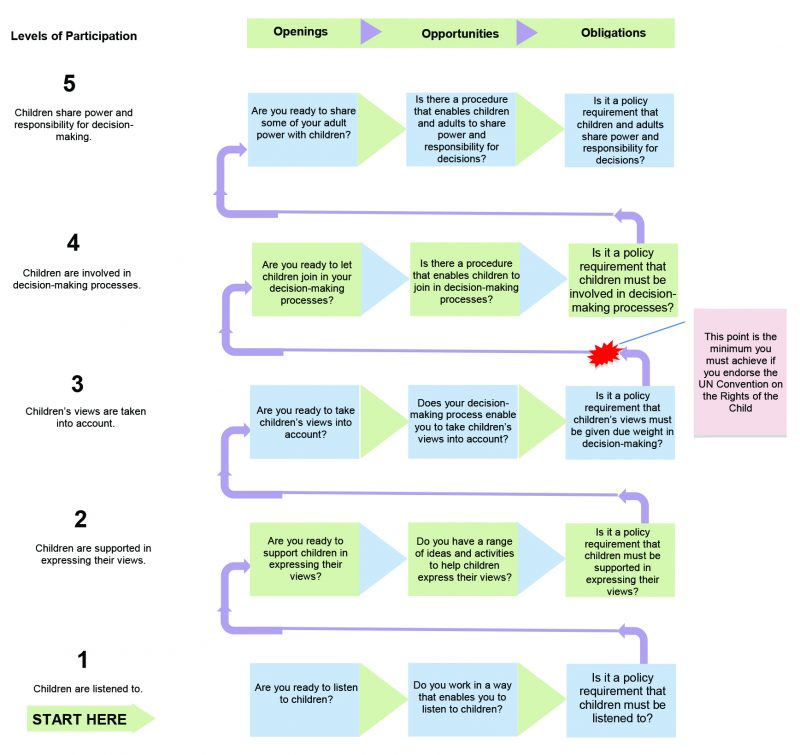

Harry Shier designed his model (2001) to be an additional contribution to the burgeoning literature on the theme of active participation not as a replacement for the work that had come before, particularly the seminal work of Arnstein and Hart. His Pathways to Participation, shown below, demonstrates the stages of development that decision-making processes take when working with children; it is perfectly possible to substitute ‘youth’ or ‘citizen’ for ‘child’ and find the process still applicable to wider audiences.

Shier identifies five levels of participation (2001: 110):

His model also acknowledges the potential for differences between organisations and individuals: for some it may be about commitment; there will be structural issues inherent within an organisation that may militate against effective participation; there may be ethical or ideological constraints; or it may be a matter of raw power, of not wanting to let go. The model provides an aid to identifying potential difference based on levels of commitment: openings, opportunities, and obligations.

Openings are simply starting points but progression may not be possible: perhaps because something other than commitment is missing or not yet in place. Opportunities arise when the necessary elements are in place and ready: Shier identifies, for example, staffing and other resources; a need for appropriate skill and knowledge, and requisite training; and the potential need for improved procedures or service developments. The Obligation stage is achieved when people and organisations combine to make and implement child-friendly engagement as policy.

By reference to the model, it can be seen that it poses a series of 15 questions; these should be addressed both by individuals and organisations to plot location. It is likely that there will be differences between where individuals are regarding evaluation of their practice and how the organisation perceives its position; this is good since it presents an Opening that enables dialogue about potential Opportunities, and identifies a route to creating possible Obligations.

The process of identifying locations on the Pathways to Participation model can be an emotional exercise that should be handled with sensitivity; acknowledging difference, committing to change, and enabling change to happen, are time-consuming processes. All change requires acknowledgement of personal and organisational standpoints; and an understanding and acceptance of the need for negotiation and the achievement of consensus.

At each Level within the model you will see three discrete stages (the boxes from left to right). Each stage moves through a different expectation of commitment and places greater demands on personnel and organisation alike.

Moving up through the Levels increases the commitment intensity and shifts the power balance incrementally. Shier advises that at every level, and at each stage, the techniques applied should be age-appropriate and that the language used is familiar; he further advises that working with groups with communication disabilities will require adjustments to ensure genuine engagement is possible.

Although children have a right to be heard it is not automatic that just because they say so that things must change. The voices of the powerless should be heard but must then be balanced against the much more difficult concept of ‘the greater good’; it is inevitable that some may be disappointed. No one said it was easy!

Engagement, whether involving children, young people, or older citizens, is deemed to be beneficial. Shier’s analysis of the benefits include (2001: 114):

Improving the quality of service provision, increasing children’s sense of ownership and belonging, increasing self-esteem, increasing empathy and responsibility, laying the groundwork for citizenship and democratic participation, and thus helping to safeguard and strengthen democracy.

That’s quite a list of responsibilities; whilst children may not aspire to these it is more likely that older groups will. Shier wisely advises that all participation, but particularly where the practice is innovatory, requires monitoring and reviewing; to this we would add a third component, that of reflection at both a personal and organisational level.

For many organisations this may not be an easy process but using a selection of ACTIVITIES from this Handbook will contribute to more effective team working and enable changes in organisational culture. Readers are encouraged to read Harry’s article for a fuller understanding of his model.

Shier, H. (2001) ‘Pathways to Participation: Openings, Opportunities and Obligations’, Children & Society, Volume 15, 107-117.

The revised European Charter on the Participation of Young People in Local and Regional Life was formally adopted in May 2003. The Charter is just one manifestation of the Council of Europe’s youth policy: starting from a commitment to equality of opportunity, the Council’s aim is to provide experiences that develop knowledge, skills, and competencies, to enable all young people to play as full a part as they wish in shaping their futures. One of the initiatives developed to support implementation of the Charter is Have Your Say! a practical manual that explores many facets of participation – definitely a recommended read (there’s a link at the end of this section).

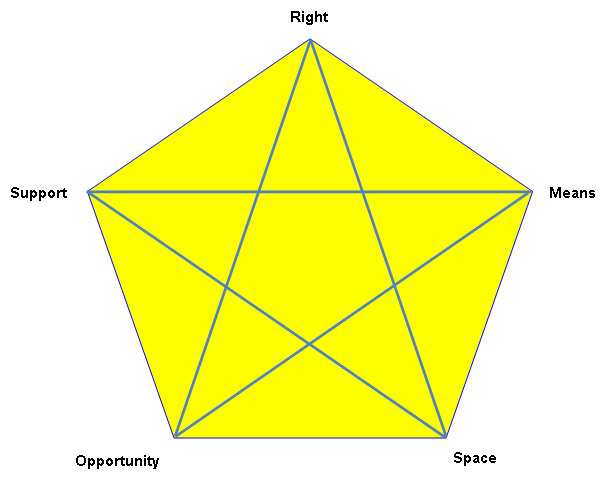

The Council of Europe’s RMSOS Framework features those key elements that have been identified as necessary to critically engage young people in meaningful involvement at local and regional levels; it is not difficult to extrapolate how the philosophy and practice might be applied at national, and international levels. The Charter’s regard for participation is based on five keywords that form the fundamental construct: Rights, Means, Space, Opportunity and Support. Whilst each element is described separately (see below), success is predicated on the conscious interconnectedness and interrelatedness of the whole; they represent discrete elements of support that combine to enable young people to engage with, and achieve, change.

The RMSOS Framework is an assessment tool with which to evaluate our personal and organizational understanding of, commitment to, and practical application of active participation.

RIGHT

At its core, the Charter acknowledges that young people have a right to speak and a right to be heard. How that is manifest is dependent upon context: it may legislated for at national, regional, or local levels; it may be an agreed way of working within a community of practice, for example, youth and community workers; or it may simply be an unofficial acceptance and understanding that intrinsically the equal involvement of young people is a community good.

MEANS

The concept of means is much more politically charged than any of the other elements of the RMSOS Framework: a sufficiently supportive social security regime; quality, and suitable, education provision; secure housing; timely healthcare services; safe and attractive neighbourhoods; adequate and affordable local transport; and access to contemporary technology. These provisions might be thought of as basic rights but are undoubtedly contested and differing arrangements prevail across Europe’s diverse jurisdictions. Economic exclusion is real and the participation process loses credibility if some young people are prevented from taking part. Indeed, it may represent the interface between the classes; and resentment breeds discontent.

SPACE

Whilst it is obvious to think that a reference to space means access to a physical location, it also represents space in time to do things; and increasingly space means the virtual world. Community facilities such as schools, usually funded by the taxpayer, are often out of bounds to young people, and community groups, when school finishes. A significant space factor for participation is the institutional capacity to be inclusive, to create dedicated space for young people’s genuine involvement. Using the RMSOS Framework may offer groups the opportunity to assess the use of facilities in their communities and evaluate the commitment of institutions; that’s how campaigns start!

OPPORTUNITY

Whilst not all young people will want to get involved at any given time, barriers to exclusion should be identified and removed. The timing and location of participatory events is crucial; transportation issues, particularly in rural areas, should be considered alongside suitably accessible venues. Opportunity extends to access to suitably trained and committed youth workers to work with young people. Any structural barriers, for example, arcane decision-making processes, archaic language, or simple obstinacy should be identified and strategies developed for their removal – these may not be easy tasks!

SUPPORT

Meaningful support for participatory involvement by and for young people comes in many guises: the structural initiatives referred to above; political commitment; community initiatives that evidence acceptance and engagement; financial support to ensure equitable access and involvement by any young people that wish to participate; access to experienced and trained youth workers. Municipalities have many competing priorities for often reducing resources but a useful activity with young people is to interrogate the municipal balance sheet: highlight any budget allocation inequalities and ask questions for verification and justification; then invite politicians to meet for a conversation – that’s participation in action!

These discrete elements are part of an holistic approach to young people’s engagement; only when they are in equilibrium will participation be authentic.

Goździk-Ormel, Ż. (2008) Have Your Say!, Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

http://www.coe.int/t/dg4/youth/Source/Coe_youth/Participation/Have_your_say_en.pdf (accessed 13th February 2017)

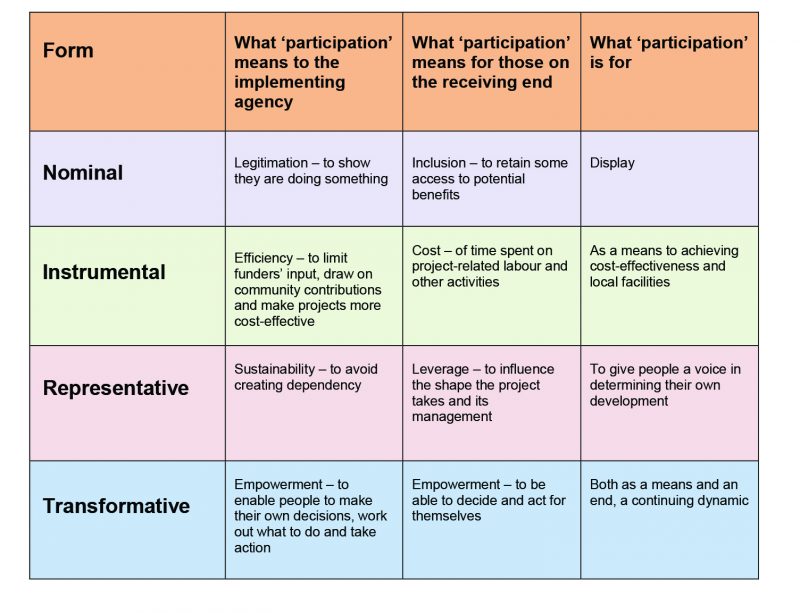

Sarah White’s (1996) Typology of Interests may suggest a ladder-like structure not dissimilar to those of Arnstein, Hart, and others, examined earlier. However, her work seeks to elaborate, much like Pretty’s work, that when considering participatory practice the observer should consider the motivations of those with power. Indeed, we would suggest that Arnstein’s ladder metaphor has, along with Hart’s identical device, had the effect of misdirecting generations of activists into only seeing the representation but not considering the accompanying narrative. White succinctly illustrates the competing motivations for different players, or actors; their conflicting ideological perspectives can be clearly defined using the chart below.

As White’s chart so graphically illustrates, the potential for conflict, and the exposition of contradictory motivations, represent a narrative of challenge. Those with power anticipate challenge, maybe even defiance, from those without; conversely, those who perceive themselves to be without power may consider conflict to be healthy and a necessary component of such a dynamic state of affairs. White acknowledges that participation is a political issue: it represents the interface between conflicting ideals, fuelled by self-interest, enthusiasm, and anticipation of results; the terms of engagement are critical since they represent the interests of the visible parties; discrete expectations of maintaining domination conflict with anticipation around exchanging control of power relations. White concludes by suggesting that an absence of conflict should raise questions.

If a participation project lacks engagement, passion, even conflict, then White’s cautionary conclusion should be a cause for action; it invites a forensic analysis that explores the activities of the discrete actors and a justification of process. To use the analogy of a car engine, when all the parts are laid out on a table it looks like a collection of odd-shaped pieces of metal; but when re-assembled every single part has a function that contributes to the singular purpose of providing motive power for a vehicle. Additionally, the engine requires external assistance in the form of fuel and a driver to navigate the vehicle. In any analysis of a participation project, whether functional or dysfunctional, it is necessary to look beyond the obvious, the visible, actors, and consider the external, maybe invisible, forces involved; are such external agents benign or malign, necessary or imposed, permanent or transitory? Perhaps the cautionary note to adopt is to consider whether the project is manipulated or emancipated, authentic or manufactured. White’s Typology of Interests leaves us with more questions than answers and provides an analytic framework from which to start.

White, S. (1996) ‘Depoliticising development: the uses and abuses of participation’, Development in Practice, vol. 61, 6-15.

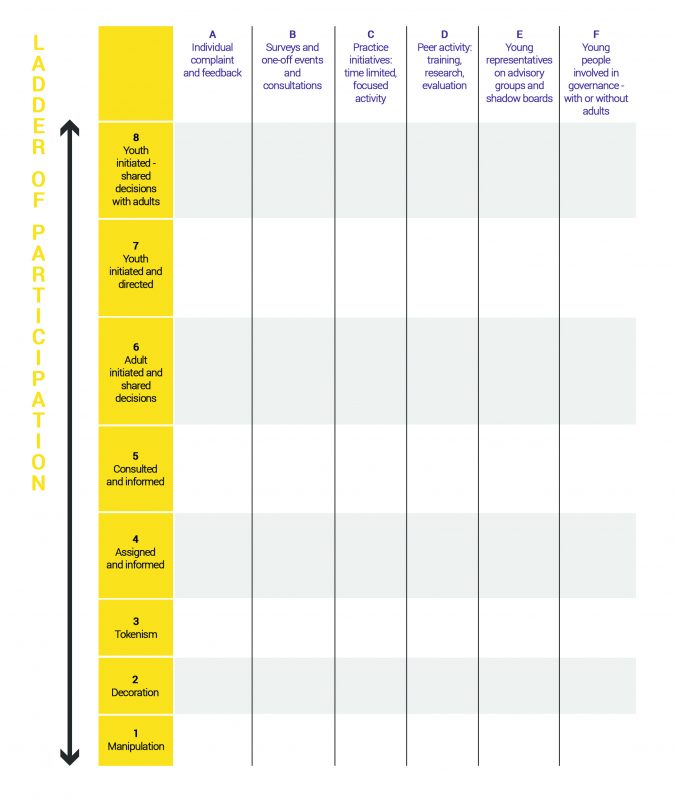

Tim Davies’ (2007) model, in the form of a matrix, uses Hart’s Ladder of Participation as a foundation: utilizing the Ladder as the vertical axis, Davies applies a series of statements along the horizontal axis to create his Matrix. The resulting grid is a tool for interrogation of either individual or organizational practice; the spaces can be populated with words or statements that illustrate how each intersecting stage provides evidence of participation. As a graphic representation it provides a strong visual image of successes whilst highlighting those areas that need work.

When using the Matrix, participants could use different colours to differentiate between one-off, short- and long-term initiatives and approaches. This continuum commences at the left-hand side, representing one-off and short-term events or activities; and progresses to capture more structured, intensive, and long-term initiatives on the right. With different projects, and diverse groups, at their own stages of occurrence or development, the Matrix offers an instant picture of the current context; but it is only a snapshot, a reference point, that hints at stories. Those stories, of success and failure, provide the detailed narrative of practice; the Matrix just gives the headlines.

A spread of engagement across the Matrix is likely to evidence an organizational practice that is dynamic, energetic, and responsive to the needs of young people; such a mix illustrates a commitment to a sustainable practice that shares the responsibility with young people. Involvement in the process leads to change. Involvement in these activities affords young people a range of opportunities: how to express themselves creatively; exposure to different forums; planning, speaking, taking responsibility; developing networks beyond just the peer group; and discovering how change happens.

With a change of words, the Matrix has applicability to other groups, for example, residents committees, trade union membership, social action groups, and many others. Support from a skilled and committed youth or community worker will assist the process; from the planned acquisition of required skills to the avoidance of unnecessary pitfalls. Davies advises that the Matrix is not static, it must work for you; whilst highlighting some of its limitation, he suggests that the model “is illustrative and further categories can be added as necessary.” (Badham and Davies, 2007: 91).

Badham, B. and Davies, T. (2007) The involvement of young people, in R. Harrison, C. Benjamin, S. Curran and R. Hunter (eds.) Leading Work with Young People, London: Sage.

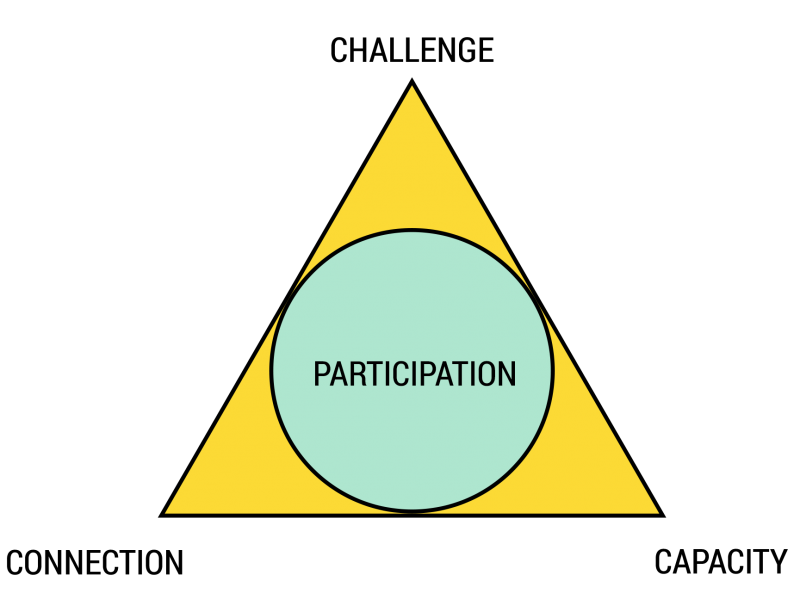

According to Marc Jans and Kurt de Backer (2002) there are three fundamental aspects that comprise a triangle of participation for young people: Challenge, Capacity and Connection. They suggest that in order for young people to ‘actively’ participate in society, these three dimensions need to be clear, understood and communicated. It is then, and only then, when each aspect of the triangular model is met that young people will be in a position to fully participate. They take a stance that young people will just in the same way as adults do, learn and reinterpret what it means to be an ‘active citizen’; this is not the place to explore what that expression means but could form the basis of a lively discussion in the context of your local realities.

Against the background of our rapidly changing present society the meaning of the notion of active citizenship changes. (…) Adults also today are constantly learning to give their active citizenship an interpretation in an informal and personal manner. There are three distinguished dimensions in this learning process that are necessary basic conditions and in varying combinations and accents steer the learning process, namely challenge, connection and capacity. (Jans and De Backer, 2002)

Challenge

Primarily, Jans and Backer suggest that young people need to be hooked by a challenge, one which necessitates their participation. This challenge can be a personal or social issue, interest, or context that the young person is passionate about, or maybe they already have a vested interest in and issue or subject and therefore are attracted to becoming more involved. This replicated Saul Alinsky’s work, Rules for Radicals (1971), around community organizing, where he suggests that the motivation for people to get involved in community organizing is first and foremost linked to some form of self-interest. With this interest peaked, the young person sees and views the challenge as an aspect of self-development, one to which it is expected they will be dedicated.

Capacity

Secondly, and this is true of the adult world as well as for young people, they need to feel that they can and will be able to cope with and have the personal capacity to deal with the challenge. If young people feel overwhelmed and ‘out of their depth’ they are less likely to be involved in participation projects as they will rule themselves out of the dynamic, as they fear that they do not possess the right skill set, maturity, or experience to take on the challenge. It is vital that young people know, and understand that they can make a difference through their involvement.

Both dimensions (challenge and capacity) are best in a dynamic balance. A lack of capacity may lead to feelings of powerlessness and frustration. A lack of challenge can lead to routine behaviour and feelings of meaninglessness. A chain of incentives and initiatives which lead to a failure is undesirable and can lead to embedded feelings of powerlessness or senselessness. Therefore we want to emphasize the importance of successful experiences. (Jans and De Backer, 2002)

Work with young people using the Triangle of Participation model means it is important that the young person recognizes their own capacity and ability to make a difference. This approach suggest a series of small and easy ‘wins’ which engender a spiral of success and goes a long way to involve young people in participatory action.

Connection

Young people need to feel, see, and understand that their involvement has some connection with that of others; that their participation is part of a bigger situation and scenario. This very basic human need is important to recognize. No one wants to think of themselves in isolation, the dynamic of seeing the connection to other movements, ideas, and events is very powerful and adds the final dimension of the Triangle of Participation. As Jans and Backer state:

Young people have to feel connected with and supported by humans, communities, ideas, movements, range of thoughts, organization,… in order to work together on the challenge. (Jans and De Backer, 2002)

Although the elements of the Triangle of Participation each have discrete characteristics, require separate support and interventions, and have the potential for conflicts and contradictions, they are in symbiotic relation to each other. They are of equal status but may require unequal resource allocation at different times and in response to context.

Alinsky, S. (1971) Rules for Radicals, New York: Random House.

De Backer, K. and Jans, M. (2002) Youth (-work) and Social Participation: Elements for a Practical Theory, Brussels: Flemish Youth Council.

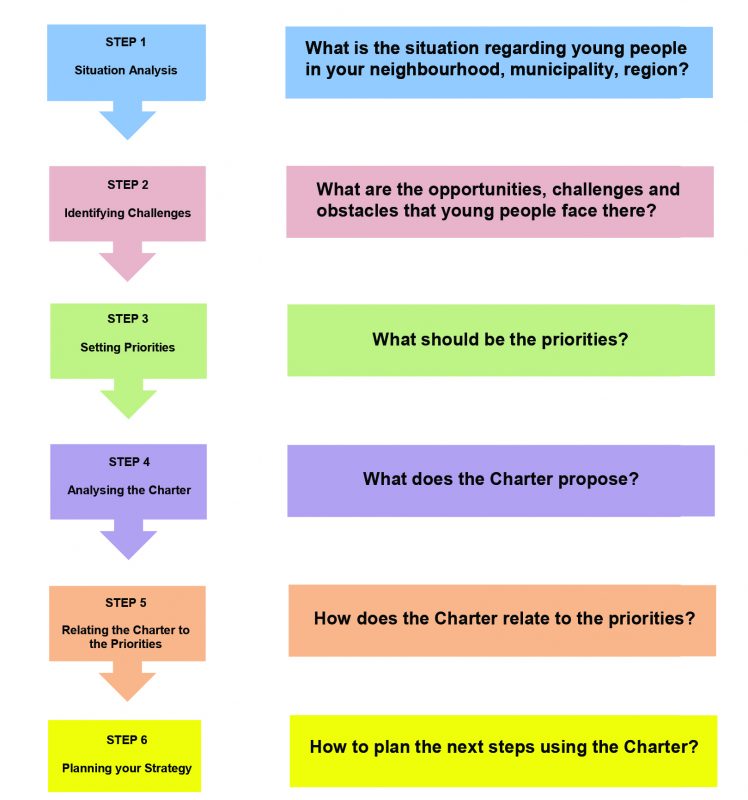

The Six-Step Model is an analytic tool that can be used at many levels: at a local project to evaluate the effectiveness of internal structures; as a community auditing device to determine priorities; as a framework to assess a municipality’s commitment to young people’s issues; or as a measure of regional engagement by stakeholders. It is not a one-size-fits-all model nor is it static; to make it work for your setting you may need to alter the key questions posed alongside each step (see illustration below).

Each step within the Model creates opportunities for young people to interrogate policies, evaluate circumstances, and assess practice effectiveness. To be an effective process certain characteristics should be identified:

Step 1

What is the situation regarding young people in your neighbourhood, municipality, region?

Be aware that everyone will have their own view be it personal, organisational, or ideological. Even if they are all right there will be differences; map what their realities look like. It may be helpful to involve an external researcher to look at things objectively before you start on any changes.

Step 2

What are the opportunities, challenges and obstacles that young people face there?

This process may promote uncomfortable realities for those in power; there may be limited opportunities for local involvement and engagement because of lack of political will or resources; there may be a genuine lack of space (see the comments in the RMSOS Framework model in this Handbook); there may be nobody with sufficient expertise to engage with the young people. This stage will require complete honesty but should be explored within a ‘no blame’ context.

Step 3

What should be the priorities?

This stage will not be easy; immediate, short- and long-term priorities can be difficult to disentangle. For example, whilst lack of adequate public transport might be an immediate problem, its solution will probably be a stubborn, long-term issue. It will require creative approaches to prevent this stage of the process degenerating into feeling of inertia. Be creative, you can do it!

Step 4

What does the Charter propose?

Yes, you are going to have to read the Charter in order to determine its relevance to your local reality. It may be that after reading you decide to substitute ‘Charter’ for some more locally relevant situation; or you might be surprised at its relevance. It is at this stage that the potential for cross-sectorial working may present itself; approach with no limits on your initial thinking.

Step 5

How does the Charter relate to the priorities?

This is where the complex elements of discrete policy initiatives have the potential to coalesce. We know that’s not a sentence destined to inspire legions of young people to engage with the participatory process but there are benefits. The separate actors and stakeholders have their own assessments of the local priorities, so start by mapping those. Firstly, look for overlaps and differences and ask how the latter can be addressed to turn them into positives. Secondly, identify relevant legislative or policy constraints and consider how they might be challenged. Thirdly, acknowledge what infrastructural arrangements are already in place, for example, youth councils or parliaments, citizen juries, or consultative forums; then identify what is missing and what might be created.

Step 6

How to plan the next steps using the Charter?

This is the good bit! Having gone through the process of Steps 1-5, considered policies and procedures, understood resource allocation, acknowledged limitations, and speculated about possibilities, now you get to plan. What will your futures look like; they will all be different? Any plans should identify the basics: who, what, when, where, how? Build in space and time to evaluate, reflect, re-organise. Be honest, not everything will work brilliantly but it may be more about process than product for the young people in the moment; creating legacy is tough but it starts now!

The Six-Step Model is one of the initiatives developed to support implementation of the Charter; Have Your Say! is a practical manual that explores many facets of participation – definitely a recommended read (there’s a link at the end of this section).

Goździk-Ormel, Ż. (2008) Have Your Say!, Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

http://www.coe.int/t/dg4/youth/Source/Coe_youth/Participation/Have_your_say_en.pdf (accessed 13th February 2017)

All of the Models presented above offer an array of choices when considering participation. Some have been designed for particular groups, for example, young people or citizen’s organisations, but you can adapt them for your own local circumstances; they must fit with your purpose, your aspirations. It has not been possible in such a brief overview to explore all of the complexities; there are many components to consider when exploring your local contexts. Attention must be paid to issues of diversity to ensure that no one is unfairly excluded; acknowledgement must be made of our differences, political, ideological, philosophical, cultural, religious, sexual identity, and more. And remember to celebrate those things that bring us together.